The backstory of ”ITISWHATITIS”

My father died in the spring of 2007. I wrote a play about it, It Is What It Is, an abreviated version of which premiered at the 2008 San Francisco Fringe Festival. Below is a bit about the real events that inspired (and were later fictionalized) in the play. There’s a lot of multimedia stuff: texting messaging, emailing, that’s a vital theme in the show: the ways we communicate differently with people depending on the medium. And the ways we communicate (via different media) simultaneously with different people.

So…

What makes the death of my father so unique?

Nothing. He was old, he was infirmed, he was ready. It happens to everyone, it’s the cycle of life, blah blah blah.

That’s the point: it’s universal. There’s nothing magical or mysterious about the death of an elderly parent. But what does make the grief-filled periods magical and mysterious are the little gems: The moments of life-saving levity that get us through the times of greatest gravity.

Several branches of my family were torn apart over issues of money when someone died or was dying. The one thing I learned about myself and my brothers — the one way in which we actually ARE alike — is that we were not going to have any of that. When the time came, everyone stepped up to the plate. No questions asked, no complaints. We did what we had to do for our father. It wasn’t easy. Hell, it downright sucked. And he made it as hard as he possibly could for us.

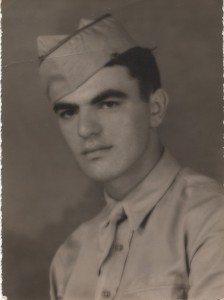

But that’s who he was: he was a fighter. He really died a month before his heart stopped. He died when he stopped fighting. When he laid there saying “take me god take me god”. When he’d close his eyes hoping, hoping hoping — only to open them and say “Christ, I’m still here”. It was actually very funny, the way he’d say it. I didn’t get my father’s humor as a kid. As an adult, I see him as one of the funniest people who ever lived. He was the the lovechild of Bob Newhart and Jake LaMotta, I guess you could say. Understated, deadpan — and deadly.

But back to those moments of levity.

Dying people say the darndest things. Chalk it up to the anger / denial of it all. Lashing out and hurting their kids is the only power they’ve got left. Everything else, their fate: out of their hands. But they can still terrify their kids into feeling like helpless children again. And thensome.

Some of the greatest things he said during that time:

“You, empty your pockets!” everytime one of us walked in the room. Empty your pockets? Was this something they said when they took someone in a back room when he was a hood growing up on the streets of New York, or something they said when they captured a POW in WWII? Empty your pockets? And he meant it. He wanted us to give back his keys, his money — things I assure you were NOT in our pockets.

He wanted us to call him a taxi and a plane to get him out of there. Taxi: okay. But a plane? A plane?

You wonder what’s going on in their head when they say shit like that. But you know, it’s never the time to ask.

But the best, the all time classic, is when he had the three of us together, tearing us a collective new one. And he blurts out — and I quote — “You’re all male prostitutes, the three of yous”. Now first of all, I’m a woman. Secondly, my brothers — well, let’s just say if they actually WERE male prostitutes, you’d never ever, ever never guess. Maybe I’m wrong.

Oh, and then there was the time when the old guy down the hall took me for a prostitute (female, I assume). I was standing outside my father’s room, on the phone with a friend. I made a point of wearing a dress and looking very pretty everyday I was there, for my daddy. And this old, very lucid-looking guy rolls by in a wheelchair. He’s one of the more spritely guys in this place. He looks at me with them porkchop eyes and says “Hello, pretty lady!” So I, in turn, said “Hello!”

Well, I guess he went to the bingo hall and told some tales. Because 15 minutes later, there’s a knock on the door. No one knocks in this place. I answer it, it’s a different old guy. This one not so lucid. He’s looking at me like I’m the first woman he’s seen since the war who’s not a nurse or in a wheelchair — and he’s not sure what to make of that. Finally he says:

“This 204?”

I didn’t know what the hell he meant at first. Then I realized there was a placard next to the door. My father’s room number. Who knew? It was just the third on the left to us.

“Yes, this is 204.”

“You 204?”

“Um, yeah, I guess that would make me 204.”

“Can I come in?”

“What? No, you can’t come in.”

“Why not?”

“Because I’m in here with my father, that’s why not.”

“Really?”

“Really.”

So… That’s the way it is?”

“Yeah, that’s the way it is.”

“Well, gee. That’s too bad”

And he disappeared down the hall, to the faded tunes of the player piano…

But even after my father gave up the fight, there were still some killer moments in there. He was having one of those “Christ, I’m still here?” afternoons. He asked me what he should do. I told him his options were pretty limited, that he could try holding his breath. So he did. But that just aggrevated his respiratory infection and made him cough uncontolably – apparently he awakened a dormant volcano of dry green mucous in his lungs, and once it started , there was no turning back. Of course he was so dehydrated the stuff wouldn’t move, and he couldn’t really drink liquid, so he’d have to suck on a piece of ice ‘til it melted, let the water loosen up a small amount of phlem, and spit. Repeat. For a good twenty minutes. I stood there the whole time, spittoon in one hand, towel in the other. I think he coughed up his own bodyweight in mucous. I asked him to stop holding his breath after that. (fortunately, that scene never made it to the stage).

Or the time I was leaving and he said wistfully “I want to go with you”. I’m pretty sure that my father never had a wistful moment a day in his life before this, so I’m so happy I was there for it. I told him to close his eyes and float out with me. AND HE ACTUALLY DID. Close his eyes, I mean. I hope he floated out with me. You’d have to ask him. But it was so sweet that he tried.

To kill time between these moments actually worth remembering, I started writing them down — just to be sure I’d remember. It’s hard to eat, read, anything when you’re sitting in a nursing home with one crap channel on the TV. That kind of sleep deprivation makes most all activities requiring an iota of concentration moot. Armed with my laptop (and no wifi), I just started jotting things down. Observations. Drafting emails I would later send when I could get online. I also started taking pictures of everything and anything within my day. With one exception: I did not photograph him. He would never want to be remembered that way, and besides, for better or for worse, I’ll always have the image of him shriveling up and dying in slo-mo burned on the back of my retinas for life.

No, just little things and moments of beauty that I might not otherwise appreciate. Having a camera made me seek out beauty. Like the beauty of the older black couple in a ’55 T-Bird convertible on Easter Sunday, old school blinged out. I ran three red lights to catch up with them. They had to think I was law enforcement, chasing after them with a camera hanging out the window. And when I finally caught up?

“Excuse me, you two are just so fabulous, would you mind if I take your picture?”

“No Pictures.”

“Look, I’m just having a really tough week and you’re the first thing I’ve seen in days that’s made me smile and I would really appreciate it if I could have a picture of you to remember….”

“No, I’m sorry, No Pictures.”

“Listen, we just put my dad in a nursing home cos he god diagnosed with terminal brain cancer and he’s 83 and I just want one picture cos you’re the only sight that’s made me smile all week.”

(I can’t even finish tht schpiel without breaking down and crying like a baby. Plus I know the light is about to turn green, and my opportunity will be gone)

“You go right ahead baby, you take as many pictures as you like”.

Or my Las Vegas touchstone, the mountain ridge to the west that I call “my tooth” because it looked just like my first permanent tooth that came in when I was 4 or 5 or whenever the hell that was. It’s the one thing I know I can count on in Vegas not to change.

But the best is probably Howard. One day I looked out the window in my father’s room onto the terrace and saw a desert tortoise. Not rare in a desert, except that this terrace was fenced in. Since my father couldn’t see it, I thought I’d find my way out onto the terrace to take a picture of it for him. To get out onto the terrace, I needed to go through the lunchroom, then through the kitchen, then through an administrative office. There were a couple of staffers there, and when I told them why I needed to get out onto the terrace, they delighted “Oh, Howard’s out!” He’d been MIA for a while (which made no sense, since this terrace is @ 200 sq. ft.; but I digress). So they got all giddy and ran to the kitchen to get some lettuce to feed hungry Howard. A few elders were in the dining room and were curious what all the commotion was about. Apparently, this is the most exciting thing to happen in this place for a while, because before I knew it, there was a bottleneck of wheelchairs trying to get out onto the terrace to see Howard eat. And all because I was packing a camera.

(On principle I’m usually opposed to photographing sunrises & sunsets. But this one came about on the morning of the last day I knew I would ever see my father. Couldn’t sleep for some reason, and then I realzed the sun was rising and I hadn’t seen a sunrise in too long to remember… and the camera just followed me there.)

(On principle I’m usually opposed to photographing sunrises & sunsets. But this one came about on the morning of the last day I knew I would ever see my father. Couldn’t sleep for some reason, and then I realzed the sun was rising and I hadn’t seen a sunrise in too long to remember… and the camera just followed me there.)

My oldest brother Charlie, lived with our father the past 17 or so years. Going through our father’s things, he found a stack of cards and letters to our father, from me. Dating back to when I was 10 years old. Our father never took time off from work to vacation. So every family trip we took, I sent him a postcard or a letter. Nothing too sentimental. Just documenting our travels for him. And I did this up to and including my moves (now well into my adult years) to San Francisco, Melbourne (Australia), London, and back to San Francisco. I never even realized that’s what I was doing. But I did — and he saved every one, in order.

And so I read them all, in order. And each detail in each one jarred my memory. I’d forgotten much, but it came right back when I read it. Which made me wonder: how much other stuff have I forgotten for good, because I didn’t write it down?

And there I was at his bedside, still documenting away.

And that got me to thinking about those emails I was drafting, and those notes and pictures I was taking while my father was dying: I was capturing the things I wanted to remember. Not the full picture. Busted! I’d written to my dad the stuff I thought he’d want to hear, or at least the stuff I thought worth hearing at the time. I was now doing the same, both content-wise and stylistically. I was choosing what to document and using my best voice, tweaking sentences, rearranging paragraphs, grasping for obscure modifiers. To prove to readers (and myself, when I look back): “I can write”. Or maybe “I was cool”, or “I was smart” “clever” “sensitive”. I’m not sure. Kinda like what people do today on Blogs, on Facebook, and in Photoshop. But I digress…

My brothers, on the other hand, don’t seem to remember a goddamn thing. I don’t know if it’s because they didn’t keep a diary as I always did as a kid, or they just don’t reflect much. But I went back to see them several months later to do a little more digging, for ideas for the male characters in the show. And I found that any bonding that my brothers and I were ever going to do in our lifetimes was that month of our father dying. I had my chance, it’s gone. They had nothing. I recalled to them memories I had of things that happened TO THEM when we were kids that I thought affected them for life. No recollection.

So as you know, he died. My brother Michael had left the room 15 minutes earlier. I’d left to return to San Francisco 6 days earlier. My brothers phoned me everyday from his room, and would put him on the phone. You could tell he was between 2 worlds: the present and some shaken snowglobe of life memories. He sounded weak yet abstractly optimistic? There’s no other way to describe it. That final call was a relief. No more “take me god take me god.” No more “Oh Christ, I’m still here?” Yeah, honestly, but the time the call came, relief.

And then the family reunion that was his funeral. He wanted to be buried in the family plot in New York. We have a family plot? Who knew? So we 4 (my 10 year old nephew Nicholas came along for the ride) flew back east, and saw all our Big Fat Greek Cousins we haven’t seen in many, many years. It was good. It was sad, sure. But it was really good. And of course, the family name is misspelled on the mausoleum. Which couldn’t be a more perfect ending. Hey, It Is What It Is.